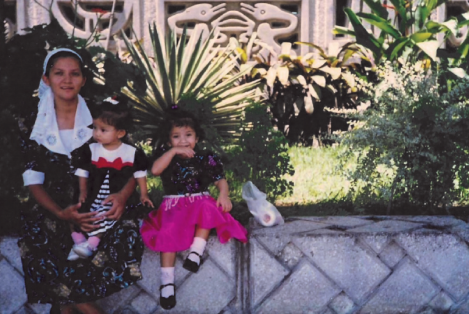

The author, center, with her mother and older sister in El Salvador, before they made the journey to Long Island, New York for her life-saving surgeries. Photo provided.

by Evelyn Sanchez

Committee on U.S.-Latin American Relations (CUSLAR)

In our aging apartment on Long Island, during hot summer days, my sister and I would place our hands flat against the floor to allow ants to crawl onto our hands. From there, we would watch them as they moved along our arms with no definitive trail.

During several holiday seasons, my family received gifts and food from our schools and local organizations. One year, in the days leading up to Thanksgiving, the bell rang. My mother opened the door to find a turkey and a box with clothes and Barbies and other toys. As she looked around, she caught a glimpse of a police car driving off. We opened the box and unpacked it with excitement.

Despite these memories and the reality of inadequate housing and not enough food or clothing, I wasn’t aware I lived in poverty.

My parents had grown up in poverty in El Salvador. They weren’t able to finish elementary school. Instead they had to go to work to feed themselves, and contribute to the household income. Their families had also experienced the brunt of the civil war that plagued El Salvador for over a decade; this upbringing drove their determination to provide my sisters and me with a better life.

My father worked as a courier between El Salvador and the U.S. He would also spend time in the United States working as a as a farmworker in Florida and as a cook in Long Island. We didn’t have much, but we had enough to eat. Then one day when I was two, he was robbed at gunpoint. A month after that, my mother was told that I needed two open heart surgeries if I was going to survive past the age of 5. We didn’t have the money for the surgeries, so the only thing my mother could figure out was to bring my sister and me to the U.S.

After a month of traveling on buses, trucks and on foot, we were face to face with the Rio Bravo. We sat on a tire and crossed the river. Once across, we set foot in the U.S. and began walking inland. Three hours later, our group ran as immigration officers approached us and we were caught. We were taken to an intake office in Brownsville, Texas. Then we were directed to a church where we received help. We stayed at a church member’s house for a week. After that, we were able to join my father on Long Island.

There, he worked in a wire factory during the day and as a janitor at night. My mother also got a day job in a factory, as they had to cover our growing expenses, pay my father’s debt and pay the debts we had incurred through our journey here, plus immigration attorney fees.

We started school within a couple of years and were placed in ESL classes. Our dad would take us to the public library every weekend. We would take out several books, as well as movies to improve our English and learn new things like sign language. Though we had limited resources, our parents were able to instill in us an appreciation for learning.

During this time, we had to check in at immigration court every three months. In 2000, the LIFE Act was passed which allowed us to apply for our residency. Then in 2001, El Salvador was hit by a 7.6 magnitude earthquake and powerful aftershocks. The destruction made it unsafe for Salvadorans to return and the country was designated for Temporary Protection Status by Congress. We hired an attorney who helped us apply for this protection.The LIFE Act combined with TPS granted us protection until we were able to become residents, through my father. As minors, my sister and I automatically became citizens and thankfully, my mother has also able to gain her citizenship.

Meanwhile, my mom had my younger sister and began to have health issues, at which point she left work to care for the three of us. My father’s jobs remained our only source of income, but we were able to get by.

Seven years later, my mother was diagnosed with cancer on the day she gave birth to our youngest sister. My father took her to chemotherapy two to three times a week. The hospital was over an hour away and my father taking her was the most economical option we knew of. So, he took some time off from his day job.

During this time, financial hardship was compounded by emotional hardship. We made ends meet only because of the help we received from friends and our church. They would bring us money, clothes, food, diapers and prayers. One of our neighbors would also care for my baby sister at night so that my father could get some sleep.

Several months after returning to his day job, my dad was laid off. The factory had been moved to another state. He couldn’t find another job. My parents became overwhelmed by the expenses. Despite working, my parents’ income has always been below the poverty line. They were aware of some of the government assistance programs but they didn’t want to apply; they didn’t want to be seen as needy. However, the financial stress made them apply for food stamps. These helped us for several years.

My family’s experience is but one example of the multiple struggles the poor in this country face, even if we never considered ourselves poor.

The Misconceptions

Poverty is often misunderstood, both in terms of its causes and the breadth of its impacts. In Pedagogy of the Poor, Willie Baptist and Jan Rehmann analyze the conceptual ways in which it is often understood. It is considered an unfortunate, yet inevitable phenomenon. In underdeveloped countries, poverty is said to be the result of not being “fully integrated into the world market,” problems supposedly fixed by technology and industrialization. Some argue that poverty is caused by poor individual decisions that characterize a “culture of poverty” and are deepened by welfare programs which encourage such decisions including single parenting. Such understandings remove the responsibility from the poverty-producing systems.

In the United States, particularly, poverty is overshadowed by the enduring myth of the American Dream. The prevailing notion of this dream is that with hard work comes success. However, the experience of my family and millions of others show that hard work doesn’t necessarily mean avoiding poverty.

Through the media, poverty is largely portrayed as a problem of non-Whites. Of the images corresponding to the 474 stories regarding poverty published in major news outlets including Time and U.S. News and World Report between 1992 and 2010, over half pictured African Americans. During this time, African-Americans made up only 25 percent of the poor in the United States. Media portrayal thus has helped to shape a racialized conception of poverty that is incorrect. Though it is true that poverty is disproportionately experienced by African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics. Still, most people living in poverty are non-Hispanic whites. They make up 42% of the poor.

The Extent and Realities of Poverty

In addition, poverty is also understood as less widespread than it is. With the United States listed as the wealthiest country in the world, poverty would appear to be a distant problem. Official poverty statistics are increasingly inadequate to describe the current reality.

When low income households – those with an income less than $48,680 for a family of four – are considered, the number of people facing economic precarity rises to 95.2 million – 45.2 percent of people and 44 percent of children. When the possibility of experiencing economic hardship over one’s life course was considered in 2015, the number rises to 4 in 5 people experiencing unemployment, reliance on government assistance or at least one year in poverty or close to it by the time they are 60.

Nearly half of households, 44 percent, would not be able to afford a $400 emergency without borrowing or selling something. This indicates the risk that poverty poses for households beyond the poor and low income.

This widespread poverty transfers over to the makeup of welfare beneficiaries. Over one fifth of people in the U.S. receive government assistance and people of all racial and ethnic groups are beneficiaries of poverty reduction programs. Assistance is not limited to minorities. More white working-age adults without a college degree are lifted above the poverty line by these programs than any other racial or ethnic group. Whites also make up the majority of people receiving benefits like food stamps.

Poverty is also not confined to urban areas. In the past several decades, rural poverty has exceeded urban poverty. More recently, as gentrification pushes lower-income families out of cities, poverty has dramatically grown in the suburbs with more poor people living in suburbs than in cities and rural areas.

Another reality is that poverty is also a phenomenon experienced by the working class. As one of the hardest working people I know, my father has always worked and for most of his life, worked more than one job. My mother, likewise, is just as hardworking. The poor do work.

Of working-age adults living in poverty, 45% were part of the labor force in 2014 – with most of those not working being either disabled, students, caregivers, or in retirement. When it comes to welfare recipients, 73% of public benefit beneficiaries were part of working families. Still, growing expenses, especially in healthcare, education and housing, render these jobs insufficient to meet basic expenses. Though skilled work and success are rightly associated, policies that cite job training as a solution to poverty place too much faith in non- existent quality jobs.

Last year, almost half of the U.S. workforce had jobs that paid under $15 an hour, and one in four low wage workers did not have at least one paid sick day. These work conditions cross racial lines. The majority of low-wage workers are White while African American and Hispanic workers are more likely to have such jobs – 53% and 60%, respectively. The majority of these jobs are held by women.

Realities as a Product of Institutions

Extensive economic hardship is tied to institutions that are fundamental to society. In the United States, the immigration system , which was one of the systems my family first came in contact with, is but one of the many institutions which help create, maintain and reproduce poverty.

Immigration has been essential in the economic growth of the United States. In addition to the accumulation system based on slave labor, genocide and stolen resources, immigrant labor fueled industrialization and growth. Unfortunately, despite the contributions of immigrants to build this country, immigration law is an obstacle for individual and societal development.

The Immigration System and the Criminalization of Humans

The Constitution, as the founding document of the United States, reads, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Reality contradicts our country’s deepest values espoused on paper. Ever since the application of law to immigration, the rights of some to achieve life, liberty and happiness have been prioritized over that of others.

When U.S. citizenship was established by the U.S. Naturalization Act in 1790, it was first only attainable by free white men and was not guaranteed by birth or naturalization. The first restrictions on the entrance of noncitizens targeted convicts and prostitutes, the mentally unstable, and those likely to become a public charge. Further restrictions stemmed from racial tensions created by the influx of Asians in the 1880’s, which led to the Chinese Exclusion Act, banning immigrants from China. In 1981, the basis for exclusion was extended to health, poverty and polygamy.

In the following century, Asians were again targeted. Attempts were also made by leaders to exclude persons of African ancestry, though they proved unsuccessful. Literacy was added as a requirement. Quotas were used to favor immigration from western and northern Europe. The repatriation campaign during the Great Depression led to the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Mexican Americans including U.S. citizens.

As immigration laws developed in the twentieth century, they cemented a system that prioritized family relationships and skills. Today, the complexity of the immigration system that has since developed provide limited options for immigrating to the United States legally present obstacles for individuals and families seeking a better life.

In order to come to the U.S. to live and work, individuals must apply for a visa. This process requires money, time and often direct relationships with documented individuals in the U.S. as well as high levels of education.

People who do not meet the requirements for these visas or cannot afford to wait years, even decades, to navigate the cumbersome system, yet obligated to help their families make ends meet, must take the undocumented alternative.

As in my family’s case, many leave their family, friends and all that they know behind because they do not feel they have another option but to use their limited resources to start a new life. Whether driven by the lack of employment opportunities, health issues, the desire to reunite with one’s family or the obligation to escape violence, war, persecution or the detrimental effects of environmental changes, immigration to the U.S. is often a means of survival. These circumstances may not grant people the privilege to follow processes prescribed by law and so, millions must take the more dangerous undocumented route to a better life.

The dangerous alternative carries the risk of losing limbs, being kidnapped, robbed, raped, murdered or disappeared as they travel. Human rights organizations have documented migrants’ difficult journeys through Mexico, where organized crime and government institutions collude to extort migrants. Despite these dangers and a U.S.-funded effort called Operación Frontera Sur to militarize Mexico’s southern border, migrants from Central and South America, and increasingly from Asia and Africa, take the risk of migration through Mexico. Individuals would not choose to take this route if they felt they had another option.

Immigrants also face the risk of death. Thousands of lives have been lost and the presence of more physical barriers drive immigrants to take even more dangerous routes. Since the implementation of Operation Gatekeeper in 1994 – among other measures taken in the militarization of the border with the aim of stemming the entrance of undocumented immigrants across the U.S.-Mexico border, coinciding with the development of NAFTA – around 10,000 people have died. This year alone, 239 deaths were reported between January and July.

Of those immigrants who make it to the United States – either with visas or the undocumented route – 380,000 to 442,000 people, including unaccompanied children, are held in immigration detention each year. Many are held in legally sanctioned and funded prisons run by private corporations, where a lack of oversight enables abuses. If and when released, undocumented immigrants are kept under surveillance through frequent check-ins and more recently and increasingly, ankle monitors. The search for a better life is met with punishment and criminalized.

The lack of documents also limits the opportunities they can take advantage of and makes it so that they must, again, take the more complicated route to take advantage of the opportunities that are available. They have less protection, both in formal or informal employment. Like my parents did, immigrants often take lower paying jobs and their household incomes are 20% lower than U.S. born families . They constitute a large portion of the workforce in jobs in the agriculture and housekeeping sectors. Low-paying jobs already provide less security and usually few or no benefits. The lack of documentation adds a layer of vulnerability to immigrants as it hinders access to social benefits that may supplement low income.

Despite contributing to society, there are only a few ways to acquire documentation and they are limited to certain people. Programs like DACA and TPS have provided temporary protection to certain communities. Similarly, unaccompanied children fleeing the Northern Triangle of Central America and arriving at the border in recent years were allowed to make their case in front of an immigration judge so that they can stay here – though often without an attorney at their side. Immigrants do not have the right to counsel though they are allowed to hire one. However, money is needed.

These children may then be eligible to apply for a status like Special Immigrant Juvenile, which provides a pathway to obtaining residency and then citizenship. The U-Visa, marriage to a citizen, and political asylum offer the same possibilities. However, for the majority, the “lines” they are often steered towards are nonexistent.

Again, like in the case of my family, in order to be aware of and apply for these limited options, access to legal resources are often necessary. Attorneys must be contracted and application fees paid. For most undocumented immigrants, these expenses present large obstacles, and the loans they take out represent a sale of their future labor. Pro-bono and low-bono services are available but they are limited in the face of such large need.

These are among the obstacles immigrants face and which keep them at a disadvantage. Children of immigrants are more likely to live in chronic poverty than children of U.S. born families, accounting for 30% of children living in poverty, though they make up 24% of the child population. Though the majority of these children are citizens, the effects of being part of an immigrant family are seen in the disparities in opportunities and outcomes they experience, including educational. Undocumented children face further obstacles in enrolling in school and going on to higher education. DACA has provided temporary protection for thousands of children, enabling them to go to college.

The current attack on the existing protections — with the end of DACA and TPS renewal no longer extended to Nicaraguan, Sudanese and Haitian immigrants, years and even decades into their new lives, and the number of refugees allowed diminished — multiplies the uncertainty of undocumented immigrants and even documented immigrants, and their friends and families. Hundreds of thousands of people face the possibility of being uprooted yet again.

Today, more than ever, the constantly changing laws regarding immigration add to the fear and vulnerability of immigrants, especially undocumented immigrants.

Poverty and the United States

Immigration is only one of multiple systems institutionalized by law that hinder the fulfillment of the values formalized in the Constitution. Although the Constitution has not been free of formalizing inequality, the equality it references is a worthy goal. The universal nature of these values is mirrored in international law, more specifically in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights where “a life free from want and fear” is acknowledged as a right.

These values are a driving factor for immigrants like my family who make the difficult choice to leave their native land in order to achieve such a life.

However, systems like the U.S. immigration system limit the pursuit of these rights for the poor. This reality is confronted by millions in the United States and billions worldwide as poverty and uncertainty increasingly cut across geographical and social lines.

For me, the opportunities that my family and I have been able to take part in hint to the opportunities that are possible. My older sister and I have been afforded the opportunity to attend college thanks to the Higher Educational Opportunity Program, with my sister also being a Gates Millennium Scholar. Still, such opportunities often come with strings attached9, requiring some form of hardship when such opportunities which do not just include educational but also to live, should be universal.

Likewise, the availability and equal access to opportunities and resources that enable a better life are ideals that are worth pursuing globally, with acknowledgement and respect to local contexts. Unfortunately, the opportunities my family has had here in the U.S., are likely greater than the opportunities we would have had had we stayed in El Salvador. Like in the United States, there are systems in place almost everywhere – with these becoming increasingly interdependent – that hinder people everywhere, and humanity, from achieving their full potential.

As someone who is both an immigrant and poor, I have become all too familiar with many of these realities. I see fulfillment of each person’s full potential as something worth pursuing as a society.

Learn More

Willie Baptist and Jan Rehmann, Pedagogy of the Poor: Building the Movement to End Poverty (New York: Teachers College Press Columbia University, 2011)